iPS cell technology for achondroplasia

A cell is the basic structural, functional, and biological unit of all known living organisms. Cells are the smallest unit of life that can replicate independently, almost as if a human person were like an enormous puzzle, made of 100 trillion parts, the cells.

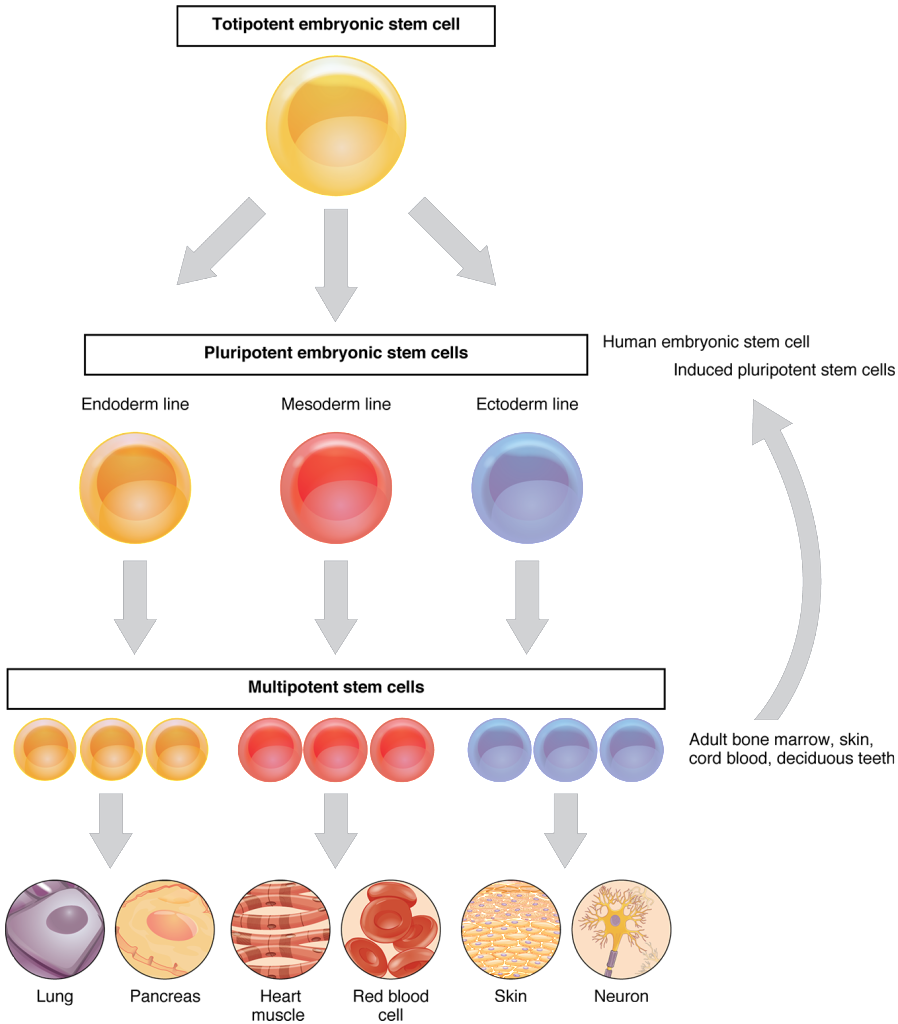

When a cell changes from one cell type to another that is called cellular differentiation. Before a cell is specialized in a specific function in the body (liver, skin, stomach cell, etc), all cells originate from a less specialized type or non differentiated cell, called totipotent, which has the ability to transform into any type of cell.

There are three basic categories of cells in the human body: stem cells, germ cells and somatic cells. Each cell in an adult human has its own copy or copies of the genome (DNA) in a specific compartment called nucleus. Most cells are diploid meaning they have two copies of each chromosome.

There are two types of stem cell:

1) embryonic stem cells - that exist in the embryo in development during pregnancy and can differentiate into all the specialized cells: ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm.

2) adult stem cells, which are found in various tissues (bone marrow, blood and fat tissue). In adult organisms, stem cells act as a repair system for the body, replenishing adult tissues. Stem cells maintain the normal turnover of regenerative organs, such as blood, skin, or intestinal tissues.

iPS cells stands for Induced Pluripotent Stem cells

The discovery in 2006 that human and mouse fibroblasts could be reprogrammed to generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) with qualities remarkably similar to embryonic stem cells has created a valuable new source of pluripotent cells for drug discovery, cell therapy, and basic research.

This was a breakthrough discovery: differentiated cells can turn back to non differentiated!

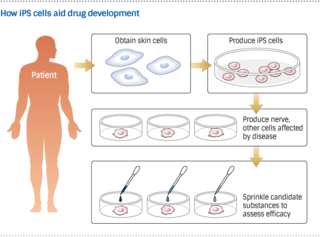

Human iPS cells take drug development in new directions

"iPS cells, promise to help bring regenerative therapies into the mainstream. But the prospect of restoring damaged tissue and organs is not the only reason to be excited. The cells' ability to grow into virtually any other kind of cell means iPS technology could also drastically change how drugs are developed.

Scientists at Kyoto University's Center for iPS Cell Research and Application and elsewhere are making headway on methods that promise to spur pharmaceutical progress"

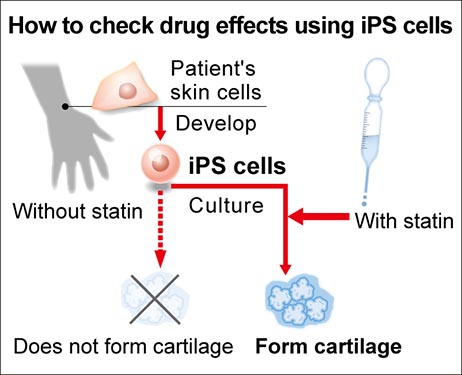

I've already published articles about statins for achondroplasia, from prof. Tsumaki's team, from Kyoto University center.

"Tsumaki's group obtained skin cells from people with achondroplasia and then researchers created iPS cells from both the patients' cells and healthy specimens. Then ran tests to see whether they could become cartilage cells. Only the healthy iPS cells produced satisfactory results; in the patients' cells, the researchers found that a certain gene was running in overdrive.

The team searched for substances that would weaken the action of the gene, and they eventually hit upon statins. When applied to the iPS cells derived from the patients, the statins enabled cartilage production.

Much scientific research is conducted this way: experimenting with a range of substances already existent to treat a known problem and check if they have a new applicability in another problem.

The fact that the candidate compound is an existing medicine is no small thing. Generally, only one out of 30,000 candidates will actually become a drug. But with an accepted, widespread substance, at least some of that uncertainty is stripped away. Side effects, for instance, are already known.

Tsumaki and his colleagues plan to start clinical trials on statin-based treatments within a few years. "The research yielded important results, using iPS cells derived from patients and proving that an existing drug may be effective in treating other diseases,"